|

Suzaku has five light-weight thin-foil X-Ray Telescopes (XRTs). The XRTs have been developed jointly by NASA/GSFC, Nagoya University, Tokyo Metropolitan University, and ISAS/JAXA. These are grazing-incidence reflective optics consisting of compactly nested, thin conical elements. Because of the reflectors' small thickness, they permit high density nesting and thus provide large collecting efficiency with a moderate imaging capability in the energy range of 0.2-12keV, all accomplished in telescope units under 20kg each.

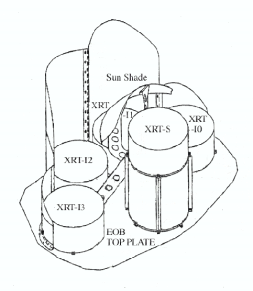

Four XRTs on-board Suzaku are used for the XIS (XRT-I), and the remaining XRT is for the XRS (XRT-S). XRT-S is no longer functional. The XRTs are arranged on the Extensible Optical Bench (EOB) on the spacecraft in the manner shown in Fig. 6.1. The external dimensions of the 4 XRT-Is are the same (see Table 6.1, which also includes a comparison with the ASCA telescopes).

The angular resolutions of the XRTs range from ![]() to

to ![]() ,

expressed in terms of half-power diameter, which is the diameter

within which half of the focused X-rays are enclosed. The angular

resolution does not significantly depend on the energy of the incident

X-rays in the energy range of Suzaku, 0.2-12keV. The effective areas

are typically 440cm

,

expressed in terms of half-power diameter, which is the diameter

within which half of the focused X-rays are enclosed. The angular

resolution does not significantly depend on the energy of the incident

X-rays in the energy range of Suzaku, 0.2-12keV. The effective areas

are typically 440cm![]() at 1.5keV and 250cm

at 1.5keV and 250cm![]() at

8keV. The focal length of the XRT-I is 4.75m. Actual focal lengths

of the individual XRT quadrants deviate from the design values by a

few cm. The optical axes of the quadrants of each XRT are aligned to

within 2

at

8keV. The focal length of the XRT-I is 4.75m. Actual focal lengths

of the individual XRT quadrants deviate from the design values by a

few cm. The optical axes of the quadrants of each XRT are aligned to

within 2![]() from the mechanical axis. The field of view for

the XRT-Is is about 17

from the mechanical axis. The field of view for

the XRT-Is is about 17![]() at 1.5keV and 13

at 1.5keV and 13![]() at

8keV (see also Table 3.1).

at

8keV (see also Table 3.1).

The Suzaku X-Ray Telescopes (XRTs) consist of closely nested thin-foil

reflectors, reflecting X-ray at small grazing angles. An XRT is a

cylindrical structure, having the following layered components: 1. a

thermal shield at the entrance aperture to help maintain a uniform

temperature, 2. a pre-collimator mounted on metal rings for stray

light elimination, 3. a primary stage for the first X-ray reflection,

4. a secondary stage for the second X-ray reflection, 5. a base ring

for structural integrity and interfacing with the EOB of the

spacecraft. All these components, except the base rings, are

constructed in 90

![]() segments. Four of these quadrants

are coupled together by interconnect-couplers and also by the top and

base rings (Fig. 6.2). The telescope housings are made

of aluminum for an optimal strength to mass ratio. Each reflector

consists of a substrate also made of aluminum and an epoxy layer that

couples the reflecting gold surface to the substrate.

segments. Four of these quadrants

are coupled together by interconnect-couplers and also by the top and

base rings (Fig. 6.2). The telescope housings are made

of aluminum for an optimal strength to mass ratio. Each reflector

consists of a substrate also made of aluminum and an epoxy layer that

couples the reflecting gold surface to the substrate.

Including the alignment bars, collimating pieces, screws and washers,

couplers, retaining plates, housing panels and rings, each XRT-I

consists of over 4112 mechanically separated parts. In total, nearly

7000 qualified reflectors were used and over 1 millioncm![]() of gold surface was coated.

of gold surface was coated.

In shape, each reflector is a 90

![]() segment of a

section of a cone. The cone angle is designed to be the angle of

on-axis incidence for the primary stage and 3 times that for the

secondary stage. They are 101.6mm in slant length, with radii

extending approximately from 60mm at the inner part to 200mm at

the outer part. The reflectors are nominally 178

segment of a

section of a cone. The cone angle is designed to be the angle of

on-axis incidence for the primary stage and 3 times that for the

secondary stage. They are 101.6mm in slant length, with radii

extending approximately from 60mm at the inner part to 200mm at

the outer part. The reflectors are nominally 178

![]() m in

thickness. All reflectors are positioned with grooved alignment bars,

which hold the foils at their circular edges. There are 13 alignment

bars at the face of each quadrant, separated by

m in

thickness. All reflectors are positioned with grooved alignment bars,

which hold the foils at their circular edges. There are 13 alignment

bars at the face of each quadrant, separated by

![]() 6.4

6.4

![]() .

.

To properly reflect and focus X-ray at grazing incidence, the

precision of the reflector figure and the smoothness of the reflector

surface are important aspects. Since polishing of thin reflectors is

both impractical and expensive, reflectors in Suzaku XRTs acquire their

surface smoothness by a replication technique and their shape by

thermo-forming of aluminum. In the replication method, metallic gold

is deposited on an extrusion glass mandrel (``replication mandrel''),

the surface of which has sub-nanometer smoothness over a wide spatial

frequency, and the substrate is subsequently bonded with the metallic

film with a layer of epoxy. After the epoxy is hardened, the

substrate-epoxy-gold film composite can be removed from the glass

mandrel and the replica acquires the smoothness of the glass. The

replica typically has

![]() 0.5nm rms roughness at mm or

smaller spatial scales, which is sufficient for excellent reflectivity

at incident angles less than the critical angle. The Suzaku XRTs are

designed with on-axis reflection at less than the critical angle,

which is approximately inversely proportional to X-ray energy.

0.5nm rms roughness at mm or

smaller spatial scales, which is sufficient for excellent reflectivity

at incident angles less than the critical angle. The Suzaku XRTs are

designed with on-axis reflection at less than the critical angle,

which is approximately inversely proportional to X-ray energy.

In the thermo-forming of the substrate, pre-cut, mechanically rolled

aluminum foils are pressed onto a precisely shaped ``forming

mandrel'', which is not the same as the replication mandrel. The

combination is then heated until the aluminum softens. The aluminum

foils acquire the shape of the properly shaped mandrel after cooling

and release of pressure. In the Suzaku XRTs, the conical approximation

of the Wolter-I type geometry is used. This approximation

fundamentally limits the angular resolution achievable. More

significantly, the combination of the shape error in the replication

mandrels and the imperfection in the thermo-forming process (to about

4![]() m in the low frequency components of the shape error in the

axial direction) limits the angular resolution to about 1

m in the low frequency components of the shape error in the

axial direction) limits the angular resolution to about 1![]() .

.

The pre-collimator, which blocks stray light that otherwise would

enter the detector at a larger angle than intended, consists of

concentrically nested aluminum foils, similar to those of the

reflector substrates. They are shorter, 22mm in length, and thinner,

120![]() m in thickness. They are positioned in a fashion similar to

that of the reflectors, by 13 grooved aluminum plates at each circular

edge of the pieces. They are installed on top of their respective

primary reflectors along the axial direction. Due to their smaller

thickness, they do not significantly reduce the entrance aperture in

that direction more than the reflectors already do. Pre-collimator

foils do not have reflective surfaces (neither front nor back). The

relevant dimensions are listed in Table 6.2.

m in thickness. They are positioned in a fashion similar to

that of the reflectors, by 13 grooved aluminum plates at each circular

edge of the pieces. They are installed on top of their respective

primary reflectors along the axial direction. Due to their smaller

thickness, they do not significantly reduce the entrance aperture in

that direction more than the reflectors already do. Pre-collimator

foils do not have reflective surfaces (neither front nor back). The

relevant dimensions are listed in Table 6.2.

The Suzaku XRTs are designed to function in a thermal environment of

20

![]() 7.5

7.5

![]() C. The reflectors, due to

their composite nature and thus their mismatch in coefficients of

thermal expansion, suffer from thermal distortion that degrades the

angular resolution of the telescopes for temperatures outside this

range. Thermal gradients also distort the telescope on a larger

scale. Even though sun shields and other heating elements on the

spacecraft help in maintaining a reasonable thermal environment,

thermal shields are integrated on top of the pre-collimator stage to

provide the needed thermal control.

C. The reflectors, due to

their composite nature and thus their mismatch in coefficients of

thermal expansion, suffer from thermal distortion that degrades the

angular resolution of the telescopes for temperatures outside this

range. Thermal gradients also distort the telescope on a larger

scale. Even though sun shields and other heating elements on the

spacecraft help in maintaining a reasonable thermal environment,

thermal shields are integrated on top of the pre-collimator stage to

provide the needed thermal control.

In this section we describe the in-flight performance and calibration of the Suzaku XRTs. There are no data to verify the in-flight performance of the XRT-S, therefore we hereafter concentrate on the four XRT-I modules (XRT-I0 through I3) which focus incident X-rays on the XIS detectors. Several updates of the XRT-related calibration were made in July 2008.

A point-like source, MCG![]() 6-30-15, was observed at the XIS aim point

during 2005 August 17-18. Fig. 6.4 shows the focal position

of the XRT-Is, that the source is found at on the XISs, when the

satellite points at it using the XIS aim point. The focal positions

are located close to the detector center with a deviation of 0.3mm

from each other. This implies that the fields of view of the XISs

coincide to within

6-30-15, was observed at the XIS aim point

during 2005 August 17-18. Fig. 6.4 shows the focal position

of the XRT-Is, that the source is found at on the XISs, when the

satellite points at it using the XIS aim point. The focal positions

are located close to the detector center with a deviation of 0.3mm

from each other. This implies that the fields of view of the XISs

coincide to within ![]() .

.

![\includegraphics[totalheight=3in]{figures_xrt/ketsuzouichi}](img107.png)

|

The maximum transmission of each telescope module is achieved when a

target star is observed along the optical axis. The optical axes of

the four XRT-I modules are, however, expected to scatter in an angular

range of ![]() 1

1![]() . Accordingly, we have to define the axis to be

used for real observations that provides a reasonable compromise among

the four optical axes. We hereafter refer to this axis as the

observation axis.

. Accordingly, we have to define the axis to be

used for real observations that provides a reasonable compromise among

the four optical axes. We hereafter refer to this axis as the

observation axis.

In order to determine the observation axis, we have first searched for the optical axis of each XRT-I module by observing the Crab nebula at various off-axis angles. The observations of the Crab nebula were carried out in 2005 and 2006. Hereafter all the off-axis angles are expressed in the detector coordinate system DETX/DETY (see ftp://legacy.gsfc.nasa.gov/suzaku/doc/xis/suzakumemo-2006-39.pdf.

By fitting a model comprising of a Gaussian plus a constant to the count rate data as a function of the off-axis angle, we have determined the optical axis of each XRT-I module. The result is shown in Fig. 6.5.

|

Since the optical axes moderately scatter around the origin, we have

decided to adopt it as the default observation axis for XIS-oriented

observations. Hereafter we refer to this axis as the XIS-default

orientation, or equivalently, the XIS-default position. The optical

axis of the XRT-I0 shows the largest deviation of ![]() from

the XIS-default position. Nevertheless, the efficiency of the XRT-I0

at the XIS-default position is more than 97%, even at 8-10keV, the

highest energy band (see Fig. 6.10). The optical axis of

the HXD PIN detector, on the other hand, deviates from this default by

from

the XIS-default position. Nevertheless, the efficiency of the XRT-I0

at the XIS-default position is more than 97%, even at 8-10keV, the

highest energy band (see Fig. 6.10). The optical axis of

the HXD PIN detector, on the other hand, deviates from this default by

![]() 5

5![]() in the negative DETX direction (see for example, the

instrument paper at ftp://legacy.gsfc.nasa.gov/suzaku/doc/hxd/suzakumemo-2006-37.pdf).

Because of this, the observation efficiency of the HXD PIN at the

XIS-default orientation is reduced to

in the negative DETX direction (see for example, the

instrument paper at ftp://legacy.gsfc.nasa.gov/suzaku/doc/hxd/suzakumemo-2006-37.pdf).

Because of this, the observation efficiency of the HXD PIN at the

XIS-default orientation is reduced to ![]() 93% of the on-axis value.

We thus provide another default pointing position, the HXD-default

position, for HXD-oriented observations, at

93% of the on-axis value.

We thus provide another default pointing position, the HXD-default

position, for HXD-oriented observations, at ![]() in

DETX/DETY coordinates. At the HXD-default position, the efficiency of

the HXD PIN is nearly 100%, whereas that of the XIS is

in

DETX/DETY coordinates. At the HXD-default position, the efficiency of

the HXD PIN is nearly 100%, whereas that of the XIS is ![]() 88% on

average.

88% on

average.

In-flight calibration of the effective area has been carried out with version 2.1 processed data of the Crab nebula both at the XIS- and HXD-default positions. The observations were carried out in 2005 September 15-16. The data were taken in the normal mode with the 0.1s burst option in which the CCD is exposed during 0.1s out of the full-frame read-out time of 8s, in order to avoid the event pile-up and the telemetry saturation. The exposure time of 0.1s is, however, comparable to the frame transfer time of 0.025s. As a matter of fact, the Crab image is elongated in the frame-transfer direction due to so-called the out-of-time events, as shown in Fig. 6.6.

|

Accordingly, the background-integration regions with a size of 126 by

1024 pixels are taken at the left and right ends of the chip for the

XIS-default position, perpendicularly to the frame-transfer direction,

as shown in the left panel of Fig. 6.6. For the

observation at the HXD-default position, the image center is shifted

from the XIS-default position in the direction perpendicular to the

frame-transfer direction for XIS0 and XIS3. Hence we can adopt the

same background-integration regions as those of the XIS-default

position for these two XIS modules. For XIS1 and XIS2, on the other

hand, the image shift occurs in the frame-transfer direction, as shown

in the right panel of Fig. 6.6. We thus take a

single background-integration region with a size of 252 by 1024 pixels

at the far side from the Crab image for the HXD-default position of

these two detectors. As a result, the remaining source-integration

region has a size of 768 by 1024 pixels, or

![]() for

all the cases, which is wide enough to collect all the photons from

the Crab nebula.

for

all the cases, which is wide enough to collect all the photons from

the Crab nebula.

After subtracting the background, taking into account the sizes of the regions, we have fitted the spectra taken with the four XIS modules with a model composed of a power law undergoing photoelectric absorption using xspec Version 11.2. For the photoelectric absorption, we have adopted the model phabs with the cosmic metal abundances of Anders & Grevesse (1989, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 53, 197). First, we let all parameters vary independently for all the XIS modules. The results are summarized for the XIS/HXD nominal positions separately in Table 6.3 and are shown in Fig. 6.7.

| Sensor ID | Photon Index | Normalization | Flux | ||

| XIS-default position | |||||

| XIS0 | 0.311 |

2.077 |

9.38

|

2.086 | 1.02 (89) |

| XIS1 | 0.294 |

2.085 |

9.73

|

2.141 | 1.59 (89) |

| XIS2 | 0.282 |

2.065 |

9.29

|

2.134 | 1.34 (89) |

| XIS3 | 0.304 |

2.082 |

9.33

|

2.062 | 1.34 (89) |

| PIN | 0.3 (fix) | 2.101 |

11.41 |

2.464 | 0.74 (72) |

| HXD-default position | |||||

| XIS0 | 0.304 |

2.079 |

9.13

|

2.025 | 1.28 (89) |

| XIS1 | 0.295 |

2.111 |

9.59

|

2.030 | 0.86 (89) |

| XIS2 | 0.282 |

2.070 |

9.54

|

2.151 | 1.22 (89) |

| XIS3 | 0.301

|

2.085 |

9.29 |

2.043 | 1.19 (89) |

| PIN | 0.3 (fix) | 2.090 |

10.93 |

2.400 | 0.82 (72) |

|

For the fit, we have adopted the ARFs and RMFs generated using CALDB

2008-07-09. These ARFs are made for a point source, whereas the Crab

nebula is slightly extended (![]() 2

2![]() ). We thus have created ARFs by

utilizing the ray-tracing simulator (Misaki et al. 2005, Appl. Opt.,

44, 916) with a Chandra image as input, and have confirmed

that the difference of the effective area between these two sets of

ARFs is less than 1%. We have neglected the energy channels below

1keV, above 10keV, and in the 1.5-2.0keV band because of

insufficient calibration related to uncertainties of the nature and

amount of the contaminant on the OBF and to the Si edge structure (see

ftp://legacy.gsfc.nasa.gov/suzaku/doc/hxd/suzakumemo-2006-35.pdf).

Data in the 1.5-2.0keV range are retrieved after the fit and shown

in Fig. 6.7.

). We thus have created ARFs by

utilizing the ray-tracing simulator (Misaki et al. 2005, Appl. Opt.,

44, 916) with a Chandra image as input, and have confirmed

that the difference of the effective area between these two sets of

ARFs is less than 1%. We have neglected the energy channels below

1keV, above 10keV, and in the 1.5-2.0keV band because of

insufficient calibration related to uncertainties of the nature and

amount of the contaminant on the OBF and to the Si edge structure (see

ftp://legacy.gsfc.nasa.gov/suzaku/doc/hxd/suzakumemo-2006-35.pdf).

Data in the 1.5-2.0keV range are retrieved after the fit and shown

in Fig. 6.7.

Toor & Seward (1974, AJ, 79, 995) compiled the results from a number

of rocket and balloon measurements available at that time, and derived

the photon index and the normalization of the power law of the Crab

nebula to be ![]() and 9.7photons cm

and 9.7photons cm![]() s

s![]() keV

keV![]() at 1keV, respectively. Overlaying photoelectric

absorption with

at 1keV, respectively. Overlaying photoelectric

absorption with

![]() cm

cm![]() , we obtain the

flux to be

, we obtain the

flux to be

![]() erg cm

erg cm![]() s

s![]() in the

2-10keV band. The best-fit parameters of all the XIS modules at the

XIS- and HXD-default positions are close to these standard values.

in the

2-10keV band. The best-fit parameters of all the XIS modules at the

XIS- and HXD-default positions are close to these standard values.

Since the best-fit parameters of the four XIS modules are close to the standard values, we have attempted to constrain the photon index to be the same for all the detectors. The best-fit parameters are summarized in Table 6.4.

| Sensor ID | Photon Index | Normalization | Flux | ||

| XIS-default position | |||||

| XIS0 | 0.321 |

2.090 |

9.55 |

2.080 | 1.24 (432) |

| XIS1 | 0.298 |

9.79 |

2.14 | ||

| XIS2 | 0.302 |

9.72 |

2.13 | ||

| XIS3 | 0.311 |

9.43 |

2.06 | ||

| PIN | 0.3 (fix) | 11.06 |

2.42 | ||

| HXD-default position | |||||

| XIS0 | 0.307 |

2.086 |

9.19

|

2.019 | 1.13 (432) |

| XIS1 | 0.277 |

9.28 |

2.11 | ||

| XIS2 | 0.298 |

9.74 |

2.21 | ||

| XIS3 | 0.300 |

9.28 |

2.11 | ||

| PIN | 0.3 (fix) | 10.80 |

2.45 | ||

The hydrogen column density (0.28-0.32)

![]() cm

cm![]() and the photon index 2.09

and the photon index 2.09![]() 0.01 are consistent with the standard

values.

0.01 are consistent with the standard

values.

The vignetting curves calculated by the ray-tracing simulator are compared with the observed intensities of the Crab nebula at various off-axis angles in Figs. 6.8-6.10.

|

We have utilized the data of the Crab nebula taken during 2005 August

and 2006 August. In the figures, we have drawn the vignetting curves

for the energy bands 2-10keV, 3-6keV and 8-10keV. To obtain

this, we first assume the spectral parameters of the Crab nebula to be

a power law with

![]() cm

cm![]() , photon

index

, photon

index![]() 2.09, and normalization

2.09, and normalization![]() 9.845photons cm

9.845photons cm![]() s

s![]() keV

keV![]() at 1keV. These values are the averages of the four

detectors at the XIS-default position

(Table 6.4). We then calculate the count rate of the

Crab nebula on the entire CCD field of view in

at 1keV. These values are the averages of the four

detectors at the XIS-default position

(Table 6.4). We then calculate the count rate of the

Crab nebula on the entire CCD field of view in ![]() steps in both

the DETX and DETY directions using the ray-tracing simulator. Note

that the abrupt drop of the model curves at

steps in both

the DETX and DETY directions using the ray-tracing simulator. Note

that the abrupt drop of the model curves at ![]() 8

8![]() is due to the

source approaching the detector edge. On the other hand, the data

points provide the real count rates in the corresponding energy bands

within an aperture of

is due to the

source approaching the detector edge. On the other hand, the data

points provide the real count rates in the corresponding energy bands

within an aperture of ![]() by

by ![]() . Note that the aperture

adopted for the observed data can collect more than 99% of the

photons from the Crab nebula, and hence the difference of the

integration regions between the simulation and the observation does

not matter. Finally, we re-normalize both the simulated curves and the

data so that the count rate of the simulated curves at the origin

becomes equal to unity.

. Note that the aperture

adopted for the observed data can collect more than 99% of the

photons from the Crab nebula, and hence the difference of the

integration regions between the simulation and the observation does

not matter. Finally, we re-normalize both the simulated curves and the

data so that the count rate of the simulated curves at the origin

becomes equal to unity.

These figures roughly show that the effective area is calibrated

within ![]() 5% over the XIS field of view, except for the 8-10keV

band of XIS1. The excess of these XIS1 data points at the XIS-default

position has already been seen in Fig. 6.7 (see also

Table 6.3).

5% over the XIS field of view, except for the 8-10keV

band of XIS1. The excess of these XIS1 data points at the XIS-default

position has already been seen in Fig. 6.7 (see also

Table 6.3).

As shown in Serlemitsos et al. (2007), verification of the imaging

capability of the XRTs has been made with the data of SS Cyg in

quiescence taken on 2005 November 2 01:02UT-23:39UT. The total

exposure time was 41.3ks. SS Cyg is selected for this purpose

because it is a point source and moderately bright (3.6, 5.9, 3.7, and

3.5counts s![]() for XIS0 through XIS3), and hence, it is not

necessary to care about pile-up even at the image core. In

Fig. 6.11, we give the images of all the XRT-I modules thus

obtained. The HPD is obtained to be

for XIS0 through XIS3), and hence, it is not

necessary to care about pile-up even at the image core. In

Fig. 6.11, we give the images of all the XRT-I modules thus

obtained. The HPD is obtained to be ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]() for XRT-I0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

for XRT-I0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

In Fig. 6.11, we also show corresponding images produced by the updated ``new'' simulator xissim (version 2008-04-05). The simulator has been tuned for each quadrant. Therefore, the simulated images look different from quadrant to quadrant. More local or spiky structures seen in the observed images, however, are not reproduced.

In Fig. 6.12, we show Point Spread Functions (PSFs) using the

data shown in Fig. 6.11 before smoothing. Note that the

core shape within ![]() is not tuned at all. The core broadening is

mainly due to the attitude error of the satellite control (Uchiyama et

al. 2007). In Fig. 6.13, we show encircled energy functions

(EEFs). The reproducibility of the EEF is important when extracting

spectra from a circular region with a given radius. In the new

simulator, the EEF of the simulations coincides with that of the

observed data to within 4% for radii from 1

is not tuned at all. The core broadening is

mainly due to the attitude error of the satellite control (Uchiyama et

al. 2007). In Fig. 6.13, we show encircled energy functions

(EEFs). The reproducibility of the EEF is important when extracting

spectra from a circular region with a given radius. In the new

simulator, the EEF of the simulations coincides with that of the

observed data to within 4% for radii from 1![]() to 6

to 6![]() .

.

XIS0

|

|

|

Studies of the stray light were carried out with Crab nebula off-axis pointings during 2005 August 22 - September 16 for a range of off-axis angles. An example of a stray light image is shown in the right panel of Fig. 6.14.

|

This image is taken with the XIS3 in the 2.5-5.5keV band with the

Crab nebula offset at ![]() in (DETX, DETY). The left and

central panels show simulated stray light images without and with the

pre-collimator, respectively, of a monochromatic point source of

4.5keV being located at the same off-axis angle. The ghost image

seen in the left half of the field of view is due to ``secondary

reflection''. Although ``secondary reflection'' cannot completely be

diminished at the off-axis angle of

in (DETX, DETY). The left and

central panels show simulated stray light images without and with the

pre-collimator, respectively, of a monochromatic point source of

4.5keV being located at the same off-axis angle. The ghost image

seen in the left half of the field of view is due to ``secondary

reflection''. Although ``secondary reflection'' cannot completely be

diminished at the off-axis angle of ![]() , the center of the field of

view is nearly free of stray light. The semi-circular bright region in

the middle panel, starting at (DETX, DETY)

, the center of the field of

view is nearly free of stray light. The semi-circular bright region in

the middle panel, starting at (DETX, DETY)![]()

![]() ,

running through

,

running through ![]() (

(![]() ), where the image becomes fainter, and

ending up at

), where the image becomes fainter, and

ending up at

![]() , originates from the innermost secondary

reflector, because the space between the innermost reflector and the

inner wall of the telescope housing is much larger than the

reflector-reflector separation. This semi-circular bright region is

only marginally visible in the real Crab nebula image in the right

panel. Another remarkable difference between the simulation and the

real observation is the location of the brightest area; in the

simulation, the left end of the image (DETX

, originates from the innermost secondary

reflector, because the space between the innermost reflector and the

inner wall of the telescope housing is much larger than the

reflector-reflector separation. This semi-circular bright region is

only marginally visible in the real Crab nebula image in the right

panel. Another remarkable difference between the simulation and the

real observation is the location of the brightest area; in the

simulation, the left end of the image (DETX

![]() ,

,

![]() ) is relatively dark whereas the

corresponding part is brightest in the Crab nebula image. These

differences originate from relative alignments among the primary and

secondary reflectors, and the blades of the pre-collimator, which are

to be calibrated by referring to the data of the stray light

observations in the near future.

) is relatively dark whereas the

corresponding part is brightest in the Crab nebula image. These

differences originate from relative alignments among the primary and

secondary reflectors, and the blades of the pre-collimator, which are

to be calibrated by referring to the data of the stray light

observations in the near future.

Overall, in-flight stray light observations of the Crab were carried

out with off-axis angles of ![]() (4 pointings),

(4 pointings), ![]() (4 pointing)

and

(4 pointing)

and ![]() (4 pointing) in 2005 autumn. Follow-up observations

covering more offset angles of

(4 pointing) in 2005 autumn. Follow-up observations

covering more offset angles of ![]() (4 pointing) ,

(4 pointing) , ![]() (8 pointing)

were made in 2010 autumn. Examples of mozaic images made with the

offset observations in SKY coordinate are shown in

Figures 6.15 and 6.16.

The stray images differ from offset to offset and from azimuth to

azimuth in the XRT coordinate. It also strongly depends on energy.

(8 pointing)

were made in 2010 autumn. Examples of mozaic images made with the

offset observations in SKY coordinate are shown in

Figures 6.15 and 6.16.

The stray images differ from offset to offset and from azimuth to

azimuth in the XRT coordinate. It also strongly depends on energy.

Figure 6.17 shows the measured and simulated angular

responses of the XRT-I at 1.5 and 4.5keV up to 2![]() . The

effective area is normalized to 1 at the on-axis position. The

integration area corresponds to the detector size of the XIS

(

. The

effective area is normalized to 1 at the on-axis position. The

integration area corresponds to the detector size of the XIS

(

![]() ). The plots are necessary to plan observations

of diffuse sources or faint emissions near bright sources, such as

outskirts of cluster of galaxies, diffuse objects in the Galactic

plane, SN 1987A, etc.. The four solid lines in the plots correspond to

raytracing simulations for the different detectors, while the crosses

are the normalized effective area using the Crab pointings. For

example, the effective area of the stray light at 1.5keV is

). The plots are necessary to plan observations

of diffuse sources or faint emissions near bright sources, such as

outskirts of cluster of galaxies, diffuse objects in the Galactic

plane, SN 1987A, etc.. The four solid lines in the plots correspond to

raytracing simulations for the different detectors, while the crosses

are the normalized effective area using the Crab pointings. For

example, the effective area of the stray light at 1.5keV is

![]() 10

10![]() at off-axis angles smaller than 70

at off-axis angles smaller than 70![]() and

and ![]() at off-axis angles larger than 70

at off-axis angles larger than 70![]() . The measured stray light flux is

in agreement with that of the simulations to within an order of

magnitude. The solution of the solid lines is incorporated into the

xissim and the xissimarfgen tools using CALDB 2008-06-02.

. The measured stray light flux is

in agreement with that of the simulations to within an order of

magnitude. The solution of the solid lines is incorporated into the

xissim and the xissimarfgen tools using CALDB 2008-06-02.

![\includegraphics[totalheight=2.5in]{figures_xrt/ae_xis_normalized_ea_withpc_Al-Ka_all}](img147.png)

![\includegraphics[totalheight=2.5in]{figures_xrt/ae_xis_normalized_ea_withpc_Ti-Ka_all}](img148.png) |

For feasibility studies of XIS data analyses of faint objects near bright sources, proposers are encouraged to simulate observations using xissim in order to determine whether the stray light flux might dominate that of the faint object or not. Proposers who do observe a target heavily suffering from stray light contamination need to handle the data with special care regarding calibration errors. Faint objects in the Galactic center and plane often suffer from stray light contamination from bright X-ray stars, and the flux of the outskirts of galaxy clusters, widely extended over the detector field of view, is sometimes dominated by stray light from the bright core.

Observers can avoid contamination from stray light if they choose the

roll and offset angles properly. Fig. 6.18 shows a

schematic diagram of the stray light patterns for a stray light source

at an azimuth angle of ![]() and an offset angle of

and an offset angle of ![]() . The square

in Fig. 6.18 corresponds to the XIS field of view. The

nominal position is located within 1 arcmin from the optical axis of

the XIS system within a couple of arcmins. The XIS field of view near

to and far from a stray light source is contaminated by stray light of

the ``Secondary-reflection component'' and the ``Backside component'',

respectively (Mori et al. 2005, PASJ 57, 245). On the other hand the

near and far sides are free from the ``Backside component'' and the

``Secondary-reflection component'', respectively. There is another

stray light free region corresponding to the ``Quadrant Boundary''

with a cone angle of 12.8 deg at an azimuth angle of 45 deg with 90

deg pitch. Observers can thus choose between three kinds of the

``stray light free'' regions. Fig. 6.19 shows pointing

positions targeting these three kinds of stray light free regions,

marked in white: the ``Quadrant Boundary'' region (top), the ``

Secondary-reflection component free'' region (middle) and the

``Backside component free'' region (bottom).

. The square

in Fig. 6.18 corresponds to the XIS field of view. The

nominal position is located within 1 arcmin from the optical axis of

the XIS system within a couple of arcmins. The XIS field of view near

to and far from a stray light source is contaminated by stray light of

the ``Secondary-reflection component'' and the ``Backside component'',

respectively (Mori et al. 2005, PASJ 57, 245). On the other hand the

near and far sides are free from the ``Backside component'' and the

``Secondary-reflection component'', respectively. There is another

stray light free region corresponding to the ``Quadrant Boundary''

with a cone angle of 12.8 deg at an azimuth angle of 45 deg with 90

deg pitch. Observers can thus choose between three kinds of the

``stray light free'' regions. Fig. 6.19 shows pointing

positions targeting these three kinds of stray light free regions,

marked in white: the ``Quadrant Boundary'' region (top), the ``

Secondary-reflection component free'' region (middle) and the

``Backside component free'' region (bottom).

![]() DET-X

DET-X ![]()

![]() [arcmin]

[arcmin]

![]() DET-Y

DET-Y ![]()

![]() [arcmin].

[arcmin].

Note that the offset direction is towards the near side of the stray

light source. The margin of 2 arcmin corresponds to the misalignment

between the optical axis and the nominal position. The Backside

component appears within an offset angle ![]() of up to

of up to

![]() (

(![]() 1.5keV). If the stray

light source is located further away than the critical offset angle,

observers can choose the Secondary-reflection component free region,

as well.

1.5keV). If the stray

light source is located further away than the critical offset angle,

observers can choose the Secondary-reflection component free region,

as well.

![]() DET-X

DET-X ![]()

![]() [arcmin]

[arcmin]

![]() DET-Y

DET-Y ![]()

![]() [arcmin].

[arcmin].

The offset direction is towards the far side of the stray light source.

If observers cannot choose any of the three stray light free regions, the possibility of contamination through stray light exists.

|